Solar in the UK is back, and faces a great opportunity. But how does it compare to the rest of the world?

Just over a week ago, the latest figures were released for registered rooftop solar PV installations in the UK. After half a decade of disappointing figures (with the caveat of a global pandemic in between), things are finally on the up. Over 160,000 installations were completed during 2022, a rise of 114% from the prior year.[1]

Large scale deployment of ground mounted and on-roof solar will be critical to achieving a net zero economy. The recently published independent review of net zero by Chris Skidmore recommended a target of 70GW of British solar should be installed by 2035. A glance at the statistics suggests that whilst we have made a good start there is a long way to go in a relatively short space of time.

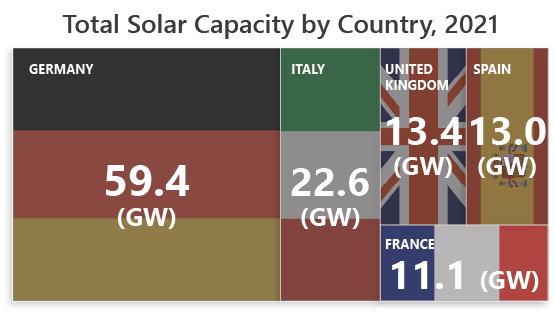

Figure 1: Total Solar Capacity, the UK and Four Largest EU27 Generators.[2]

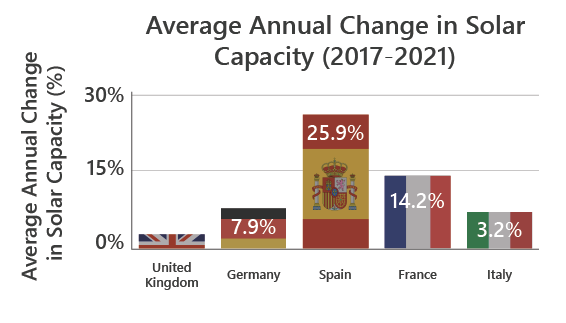

Solar companies in the UK could be forgiven for envious glances across the Channel. The UK is in a relatively strong position compared to our neighbours (excluding Germany) thanks to generous feed in tariffs during the first half of the last decade however the average growth in capacity since 2017 has been incredibly disappointing (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average Annual Change in Solar Capacity, UK and Four Largest EU27 Solar Generators.

This raises clear and obvious questions. First, and perhaps most importantly, what lessons can be learned from the slow-down experienced from 2017, and what challenges might arise as we look to reach the incredibly ambitious proposed target of 70 GW of installed solar capacity by 2035?

The Slow-Down

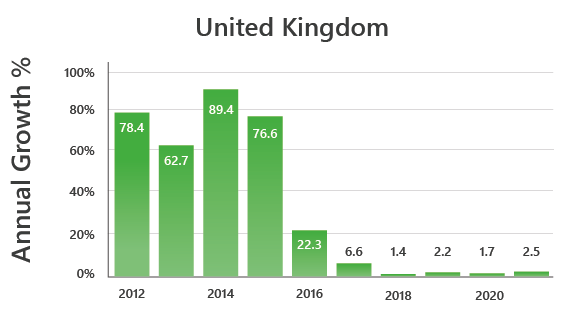

The most evident suspect responsible for the slow-down in solar PV growth in the UK is the ending of the Renewables Obligation[3] (Figure 3). This represented the end of a 15-year scheme, which has had a pronounced effect on the uptake of solar PV. Advocates of a market based approach to stimulating markets may argue that this was an expected end result of government intervention and that the market was artificially inflated to begin with.

Figure 3: Annual Growth in Solar PV Capacity in the UK

Regardless, reaching a capacity of 70 GW by 2035 requires linear growth of 4.3 GW per annum. The period from 2017 to 2022 has delivered only 0.4 GW per year, a tenth of what is required. More must be done.

Moving Forwards

Looking to the future, it is incredibly important that the recent growth highlighted prior is capitalised on, and used as a “momentum-surge”. There are a few key ways this can be achieved.

First, for the UK government to see through the commitments it has made with regards to electrification of heat, and the rollout of electric vehicles. As these become reality, the value of electricity, and therefore of self-owned generation, becomes readily apparent. There is great potential for further economic benefits of solar integrated with electric vehicles and hydronic heat pump technology.

Second, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has amplified the true value of energy security and independence. Whilst this issue has been mainly debated in the context of nations, the individuals, households and organisations have also woken up to the potential benefits. Yet, these two arguments need not operate in separate theatres. The government must recognise the important role that the consumers, private and public organisations can play in dually achieving energy security and reaching Net-Zero.

Third, but by no means finally, more must be done to highlight, recognise, and capture the tertiary potential of solar PV generation. For the hard pressed agricultural business, solar PV can offer a multitude of benefits, examples include pear farmers in Belgium using PV panels to reduce hail damage on crops.[4] For communities, solar offers not only a potentially economically viable means of producing electricity, but could help to improve the sociological idea of “community”.

Clearly, there are so many benefits to be had from greater solar PV mobilisation. Yet, don’t let this fool you. Solar PV is not a “nice-to-have” technology, but is an essential constituent building block in a Net-Zero economy. Recent positive signs have emerged, and they must be seized, and ran with, in order to drive the industry, and the country forwards.

Footnotes

[1] Solar Power Portal (2023) Last year sees 114% increase in MCS certified domestic solar installations

[2] Eurostat (2023). Electricity production capacities by main fuel groups and operator

[3] Ofgem (2017). Renewables Obligation (RO)

[4] Greenpeace (2022). Farming and solar panels can work together – here’s the proof